As I emphasised in the chapter on crises and long

kondratiev waves, see also here, channelling

resources into something useful does not happen by itself. No

government

would embark on such a far-reaching project without being forced

to. It takes something like the French Revolution, the revolutions

of 1848, the emerging trade union movement or the anti-colonial

movements to make it happen in earnest. Politicians are about

as comfortable as the rest of us and need a good blowtorch up

their arse to get moving.

In the 1930s, Sweden was one of the

pioneers of Keynesian policies, so for those who want to contribute

to change today, it may be

of interest to recall how it was that this small, remote country

was able to become a model for the whole world and, together

with the United States, inspire the post-war Kondratiev cycle

and the radical reform and restructuring policies that came with

it.

We had some advantages. The social pyramid was

fairly broad and low; since the successful peasant revolts of

the late Middle

Ages, the peasants had a mortgage on power, and both the aristocracy

and the bourgeoisie were poor by European standards. Popular

initiatives therefore did not meet with as much resistance as

in many other countries. Literacy was high, as was the relative

purchasing power of the peasantry, giving rise to a high-tech

industry around 1900 where it was relatively easy to organise

trade unions.

The mobilization wave of the early 1900s

Peasants

and the lower middle class in Sweden tended to be organised in

popular movements for temperance and freethinking since the

mid-19th century, and the labour movement that emerged with industrialisation

therefore had plenty of potential allies, including the peace

movement and the movement for universal suffrage. People

got used to setting their demands high.

Still, the beginning

was difficult. The first really big struggle, the Great Strike

of 1909, was lost by the workers. The trade

unions barely survived, and the Labour Party became extremely

cautious for a few years.

In the final stages of the First World

War, this became an impossible policy. Food shortages arose in

the warring countries and it

became more profitable to export food there than to sell it to

the Swedish urban population. Food shortages therefore began

to arise in Sweden too, at the same time as the profitability

of the war-exporting industry increased. As a result, trade unions

began to mobilise to avoid falling too far behind.

The first to take action were the workers in Västervik.

After the stone workers went on strike and demanded higher bread

rations, a general meeting of the people decided on 17 April

1917 to ration food in the town on their own and distribute it

fairly. In good Swedish compromise fashion, however, the regular

authorities were invited to the actions and all planning took

place in complete transparency. Shop stewards from the city’s

main trade unions were elected to the action committee. Among

the demands that were quickly met were increased rations and

free garden allotments.

The example from Västervik was well received

and similar actions were organised in about a hundred places

in the country,

with an estimated participation of around a quarter of a million.

In some places, things got much tougher than in Västervik.

In both Göteborg and Stockholm, street battles broke out

between workers and police. In Ådalen and Härnösand,

battles almost broke out between the military and workers armed

with dynamite, but Social Democratic leaders managed to calm

the atmosphere. In Västerås, conscripted soldiers

joined the movement. In Seskarö near Haparanda, the entire

community was occupied for a few days after a bakery was looted

as a jointly planned action and the police arrested individuals

at random.

At the same time, strikes spread among groups that

had previously been far removed from the labour movement, such

as farm workers

and women textile workers.

The movement wave was quite successful.

Influenced by this, as well as by the revolution in Russia, and

later in the winter

also in the whole of Central Europe, the government accepted

several demands that the labour movement had been putting forward

for years, such as universal equal suffrage and the eight-hour

day. Trade unions suddenly gained enormous prestige. Membership

rates, which had been around 10-20 per cent, increased rapidly.

And

the activist spirit from Västervik lasted throughout

the twenties. The strike wave of the twenties is the most powerful

in Swedish history.

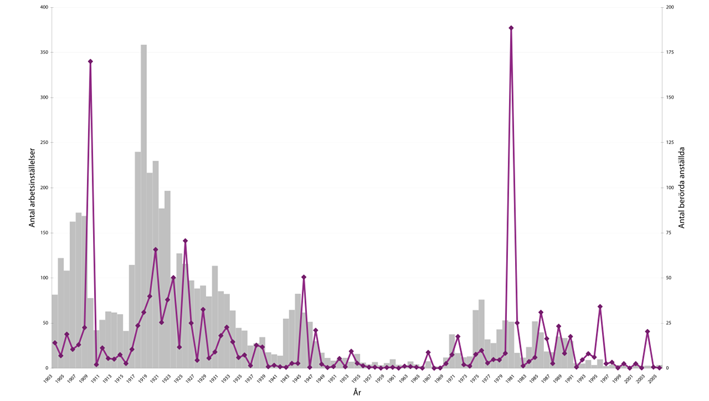

Labour conflicts in Sweden 1903-2005. The strike wave of the

1920s is visible as a large block to the left. Source: wikipedia.

The longest strike lasted seven years, from 1924

to 1931, and was carried out by forestry workers in Burträsk

in Västerbotten,

who held out thanks to the fact that they also had small farms.

The strikebreakers did not last long in the villages. In the

end, the company accepted the workers’ demands. Almost

as long was the strike at Skyllberg mill near Askersund in 1925-30.

Most

of the actions were of course shorter, but could still be quite

dramatic.

Perhaps the most notorious was the mining conflict

at Stripa near Lindesberg in 1925-27. It even toppled a government

that

did not want to agree to the employment agency of the time providing

work during a strike, but was defeated by the Riksdag on the

issue. However, the strike ended with the workers' demands for

a wage increase being met to some extent.

Less well known to posterity

are, for example, the mining strike in Malmberget in 1920, which

was won by the workers, a strike

at Scania-Vabis in Södertälje in the same year, which

unfortunately led to the company's bankruptcy, and a series of

strikes among municipal workers in Sundsvall in the first half

of the twenties, which came to nothing due to the city's relentless

use of scabs. Construction workers building the central hospital

in Västerås went on strike in July 1924, a strike

that lasted into the next year. A strike that led to riots in

Malmö began

in 1926 at A W Nilsson’s pram

factory and lasted two years, ending in compromise. And in 1921,

bakers and waiters at Bräutigam’s posh confectionery

in Gothenburg went on strike. In total, 885

strikes were organised between 1915 and 1930, with a total of

182,000 participants.

However, this strike activity was only

the engine and the most visible example of a popular movement

culture that characterised

the whole of society. Co-operative enterprises ran everything

from supermarkets to power stations. Temperance lodges organised

recreational and youth activities in smaller communities. Most

politicians of the era were educated at folk high schools, many

of which were run by non-profit and interest-based organisations

and characterised by a populist spirit. And never have so many

self-taught people from working-class and smallholder homes dominated

the culture.

As

the Norwegian trade unionist Asbjørn Wahl

has noted, the Social Democrats’ long-standing position

of power after 1932 was not due to nicely asking business to ”participate

at the table” – it was due to the labour movement

having earned respect through mobilisation and struggle. As

has been shown elsewhere, workers’ strikes don’t

even have to pay off in direct terms to produce politically positive

results – it is enough for workers to earn respect.

The business and former elites realised that it was better to

try to reach an agreement than to continue with the highest level

of conflict in the world.

”Agreement” in this case meant that

the labour movement and the business community agreed on an economic

model where

the public sector promoted full economic activity via Keynesian

economics, that the business community took care of itself within

this framework, that wages increased in parallel with productivity – and

that the government and the leadership of the labour movement

ruthlessly cracked down on those who questioned the agreement.

The

long-term erosion of their own power in this way was of no

concern to them; revitalising the economy after the speculative

boom of the 1920s was the overriding goal, everything else was

secondary.

Some popular movement theory

Can something similar be done today?

Hopefully in a less devastating long-term way?

Firstly, a general

new cycle of conditioning based on radical reductions in energy

and raw material consumption must be global.

Not least because energy and commodity markets are global. However,

as already indicated in the introduction, the let-go politics

and the lack of popular mobilisation that is its precondition

are mostly concentrated in Europe and North America. It is in

Europe and North America that governments most ruthlessly support

the financial economy over the real economy. It is in Europe

and North America that trade union organisations seem unable

to rally to anything more drastic than one-day demonstration

strikes, and it is also there that other mobilisations most seem

to take the form of ”see us – we exist”. So

that is where change is most urgently needed.

Now, the actions

or inactions of central trade union organisations are not the

decisive factor. Both the strike movement in Sweden

in the 1920s and the strike movement in the USA in the 1930s

were initiated locally, often against the wishes of the central

trade union organisations. In both Sweden and the USA, the latter

were so overwhelmed by their theoretical knowledge that recession

and unemployment put workers at a disadvantage that they did

not dare to take industrial action. The rank-and-file members

did not have this knowledge, took the fight and won – at

least in the long run.

In doing so, they

were representative of a strong global trend. Major changes have never been implemented

by large, well-established

organisations, but by local initiatives. Land reform as a global

twentieth-century policy was initiated in 1910 by some peasants

in the Mexican village of Anenecuilco who sowed maize in a field

stolen from them by the sugar plantation and mobilised other

villages to do the same. The modern labour movement in Europe

was started by a bronze casters’ strike in Paris in 1867,

which mobilised a campaign against international strikebreaking

for its protection. The Indian independence movement, key to

twentieth century decolonisation, started in earnest as a delivery

strike by a few farmers in Champaran in Bihar in 1917. Since

then, it has taken organisations to sustain a viable movement,

but the initiative has always been taken on a local issue that

had a bearing on a general problem, and by relatively few.

This holds true even for modern times. Sidney

Tarrow concludes in his thesis on the Italian wave of popular movements

around

1970 that all important initiatives were taken by local people.

Then newly formed organisations could take over, primarily as

collaborations between such local initiatives.

These then pushed the large, well-established organisations ahead

of them, primarily because these were afraid of being overtaken

by the new organisations and/or because membership initiatives

broke through the inertial self-defence of ”this is how

we have always done it” and energised the organisations.

And the relatively well-organised Norwegian movement against

privatisation of welfare started as a local uprising to save

a hospital threatened with closure, which spread across the country

to protect other local hospitals threatened with closure, gradually

supported by more and more old, well-established organisations.

And so did the strike movements that resulted in

the post-war Kondratiev cycle. In Sweden, it was the very small

workers’ organisation

SAC that coordinated at least a third of the strikes and persuaded

a reluctant LO to join in. In the USA, it was the newly formed

Congress of Industrial Organization, CIO, that coordinated the

strikes and only afterwards persuaded the old trade union centre

AFL to welcome the initiative.

So the lack of initiative today

cannot be attributed to old, sluggish, bureaucratised organisations,

however obvious this

may be. Rather, it lies in weak grassroots initiatives, and poor

conflict organisation when initiatives are taken anyway and could

give rise to something lasting.

Poor organisation can be of three

kinds.

The first is elitism. Organising is carried out,

or attempted to be carried out, by people who are convinced that

they know

better than the average participants in the movement. Frances

Tuuloskorpi has described how a possible trade union revolt

against the neo-liberal model in the late eighties came unstuck

after

it was flooded with people from overwintered left-wing sects,

all trying to foist their (different) theories and strategies

on the participants. The whole thing felt as top-down as the

traditional trade union center model they were trying to transcend,

and people turned away in disgust.

The second, spontaneism, is

probably more common and could be described as ”it will

all work out”, i.e. nobody

organises anything at all, sometimes out of laziness, sometimes

out of exaggerated hopes that it will work out spontaneously.

Since the old ombudsman-driven organisations were discredited

by the popular movement wave of the 1970s, dissidents have tended

to take for granted that all organising is evil and automatically

leads to repression and stifling of all initiatives. Major mobilisations

such as the Occupy movement in the US, the Indignados in Spain

and the mobilisations against the Greek sell-off to the EU’s

enforcers have therefore tended

to fizzle out, or at least to

behave far less vigorously than their counterparts in Sweden

in the twenties and in the US in the thirties – or equivalent

movements in the South. And therefore easier for the powers that

be to ignore.

The third is perhaps the most common, the patronage

model, or ”go

home and vote the right way in the next election”, or,

even worse, ”buy the right goods” or ”donate

a penny”. It would not be worth mentioning if it were not

so internalised among us lay people ourselves, who tend to deny

our own agency and resourcefulness, and are content to blame

the problems on the authorities and companies that once helped

create them. This may take the form of limiting ourselves to

buying eco-labelled products, or writing letters to the authorities,

or petitioning or questioning the parties. There’s nothing

wrong with doing that, but in the current situation we also need

something that is perceived as a threat. Something that, in the

context of the global system, is comparable to the popular movements

that led to the end of speculation and the beginning of a period

of production in previous eras – something comparable to

the French Revolution, the revolutions of 1848, the rise of labour

movements or the anti-colonial movements.

It is to be noted that

the patronage model is equally counterproductive whether we believe

politicians for good or bad. Even the social

democrats of the 1930s could not have achieved anything without

tangible help from their own base. The structural forces that

must be overcome are so great that a small number of parliamentarians

could not do anything on their own even if they wanted to. The

International’s words ”Our own right hand the chains

must shiver” are not an expression of revolutionary romanticism

but of down-to-earth realism. There is no other way.

What then

can be perceived as a threat? Anything that violates the order.

As

Johan Asplund has noted, in private life it is even perceived

as a threat if someone refuses to greet, because it violates

the established order.

In the public sphere, where the issue of society’s use

of resources is decided, a breach of the public order is needed

for it to count. At the same time, it is an advantage to demonstrate

in action new, better orders – it creates more respect.

Public

order offences committed by popular movements in order to gain

respect change

form rather slowly throughout history.

At any given time, they stick to a certain repertoire. This is

practical, because it is good to be able to take a collective

decision on the matter without much confusion, and that everyone

knows what should be done.

It is possibly this mechanism that is responsible for the lame

defence of social rights in Sweden – there is no common

repertoire to follow, old repertoires are forgotten, new ones

have not yet developed.

So established repertoires are good. But

it is often when people invent new repertoires that they are

most successful – provided

they find favour with those who are supposed to contribute to

them. For old repertoires eventually become part of the ’order’ and

become less effective.

At the beginning of the new era, when bureaucratic

state organisations were consolidating and waging war with each

other at great cost,

the common model of action was tax

revolt.

The villages attacked the treasurer and burned his house, and

in serious cases marched together to the capital. They were often

beaten up, but just as often the tax was reduced anyway. This

method fell out of favour in Western Europe at the end of the

17th century, partly because wars actually became less devastating

and partly because villages were fragmented and the wealthy were

given government jobs. The

last such rebellion in Sweden took place in 1743.

In European colonies, they continued into the 20th century.

Instead,

bread

seizures became

more common. This was because food prices started to follow the ”market” and

therefore sometimes tended to to rise faster than people’s

incomes. The bread riots involved the townspeople confiscating

all the bread and selling it in the marketplace for a fixed traditional

low price. This practice persisted in Western Europe until around

1850. In Sweden, as shown earlier in this chapter, it was alive

until 1917 and in South America, for example, it still is to

this day. The method is strictly localised, but when many bread

riots occur at the same time, they can topple regimes as in France

in 1789, in Russia in 1917, and in Argentina in 2001.

In the mid-19th

century, strikes become

more common than bread riots in Western Europe, as it proves

easier to raise wages than

to lower prices.

The strike as a method only becomes really popular with big industry

and the assembly line, which makes it easy to organise and carry

out – basically you just need to turn off the power. In

the US this took place in the 1930s, in Western Europe in the

1960s, in Brazil in the 1970s, in South Korea in the 1980s, etc.

In China it is taking place today, and indeed strikes there have

hit record levels since 2005.

There are also plenty of sub- and

side-organised repertoires.

Boycotts of businesses to drive them

out of business are probably ancient but got their current name

in the context of the great

struggle for land reform in Ireland in the 1880s, when, incidentally,

it played a subordinate role to going slow with the rents. Boycotts

of segregated businesses were the main initial repertoire of

the American civil rights movement, and the boycott of South

African goods in the 1980s was perhaps the most geographically

widespread political action ever, successfully complementing

the strikes that took place inside South Africa.

Site occupations

have proved powerful as an adjunct to strikes, for example in

the US labour movement of the 1930s, as a means

of preventing strikebreaking and taking the expensive machinery

hostage. Occupation has also been widely used by environmental

and youth movements, but mainly as a way to gain a physical platform

in a campaign. Farm labour movements have also used squatting

to seize land that should be feeding them rather than lying idle,

and homeless people have done so to make good use of houses left

empty for speculative reasons. A special case of occupation is

temporary ones to prevent officials and politicians from leaving

or entering a premises; pioneers here were the Indian independence

movement who called the phenomenon encirclement, or gherao in

Hindi.

And in this context, it can be pointed out that

standard repertoires can also be infinitely varied. Strikes can

be ”rolling” i.e.

moving from one department to another, they can be limited to

overtime or certain types of actions such as taking payment,

or filling in forms, they can even be ”reverse” i.e.

doing what the management forbids you to do, in extreme cases

to keep a company going when the owner wants to close down as

in Argentina in the years around 2000. Boycotts and occupations

can be combined, as can bread riots and strikes.

Each of the repertoires

has a dual purpose. Firstly, to implement their programme – cut

taxes, lower the price of bread, raise wages. But also to gain

respect and establish their executors

as a serious negotiating partner. Repertoires are expensive for

the other party, both in terms of money and in terms of reputation;

ideally he would like to avoid them in the future and may therefore

be tempted to accommodate. But more importantly, they empower

participants as agents of change at the community level, as they

see what they can do. At best, this also makes them move on and

set higher and further goals – whereas before they probably

did not even think of themselves as public actors.

As in Anenecuilco,

Champaran and Västervik, where local

action determined much of twentieth-century history.

But such

a broadening of objectives is hardly possible without local actions

being coordinated by a movement publicity. Events

are just dust that quickly settles. They must be accumulated

in institutions to become effective.

An institution is an enduring

thing that, by its very existence, guides our expectations, actions

and thinking in a certain direction,

even when nothing in particular is happening. For example, the

Swedish Worker’s Education Association ABF exists by organising

courses and programmes, but ABF also ’exists’ at

night when there is no activity going on. Our ancestors a hundred

years ago were good at creating institutions. Today we are bad

at it; today it seems that almost only the state and business

can do it.

This weakens us, because it steers our actions

and our thinking in the directions that the state and business

want.

Even movement public spheres and movement institutions require

active initiatives to be realised.

The simplest type of movement

publicity is the permanent organisation, usually a national organisation

with local groups. A permanent

organisation can have different focuses.

The earliest ones took

the form of what we now call campaigns, i.e. they were entirely

devoted to coordinating outreach activities

such as demonstrations, mass meetings, publicity, etc. on a particular

issue. Such campaigning organisations emerged in the mid-18th

century in Western Europe to complement boycotts; one of the

very first was the North American Continental Association in

1774 to fight what was perceived as illegal taxation by the British

government; early examples were also the Committee for Abolition

of Slave Trade in England in 1787 and the Catholic Association

in Ireland in 1823, which pushed for equality for Catholics and

invented the paid mass membership.

Campaign organisations still

exist, of course, and have expanded their presence dramatically

since the 1970s. Their

problem is the cherry-picking syndrome, i.e. they like to

focus on what attracts the most attention in the moment, tend

to be

parochial about

other movement initiatives, and often don’t care about

what is needed in the longer term and what is most important.

A greater focus on real permanence and comprehensiveness

in the form of a kind of parallel society first came with the

labour

and anti-colonial movements, although I suspect they owe some

debt of thought to Freemasonry, directly or via radical republican

groups such as the Carboneri in Italy in the early 19th century,

and perhaps also to churches, religious sects and in the case

of China to the traditional Chinese secret societies. However,

it was only when combined with mass membership that they became

effective, able to coordinate large campaigns, manage successes

and survive setbacks on a larger scale. Such organisations have

a greater capacity to act as movement publicity than campaign

organisations, but at the same time have a strong tendency to

bureaucratise, i.e. to devote themselves to what

is most beneficial to the paid agents and their job security and to sabotage, consciously

and unconsciously, any initiative by members that goes in a different

direction.

The latter has, at least temporarily, discredited such organisations

and they are no longer as powerful as they once were.

Effective

movement organisations can also be built around small institutions.

During the 1832-48 movement wave in England, the

privately owned Northern

Star newspaper served

as such by giving generous coverage to everything that happened

in the movement; however, this was due to the involvement of

the owner Feargus O’Connor and disappeared with his changing

interests. Such mini-institutions are also happy to appropriate

the very worst odours of NGO-ism.

Powerful actions tend to be

able to function as a public sphere during their duration. Both

the Elm

Battle and

Occupy Wall Street became centres of popular movements in their

respective places. And occupations of buildings can last long

enough to leave their mark, such as Amsterdam’s occupied

buildings in the 1970s and the archipelago of occupied cultural

centres in many Italian cities.

Since the 1972

UN conference in Stockholm,

parallel summits have acted

as movement publics, such as Cúpula

dos Povos in Rio de Janeiro in 2012;

however, such meetings are perhaps too sporadic to be really

effective.

Whatever their form, permanent movement public

spheres are needed where discussions can be held and initiatives

taken.

The shortcomings

of all their forms are problems to be lived with; if they do

not individually and collectively meet all the requirements,

new organisations will have to be created to fill the gap. The ”One

Permanent Organisation” that fixes everything is probably

obsolete; what is needed is perhaps a plethora of semi-permanent

ones that can cope with both cooperation and conflict, and which

can be supplemented by new ones as they relax. But even such

organisations must be built, actively.

And they must be built

with inclusion in mind. The neoliberal impulse, which unfortunately

includes the opposition to the neoliberal

programme, is to create brands and to compete. This only brings

minorities together and pits them against each other in a battle

of all against all for attention and prestige. And it will not

bring about the necessary social changes. These can only be achieved

with the help of majorities.

Something about identity politics

and majorities

Both the need to include majorities and the need

for co-operation and conflict argue against political parties

as movement publics.

Parties may be indispensable in turning movement mobilisations

into government policy – but there is a long way to go.

The fetishisation of parties as the ultimate form of movement

organisation and movement publicity probably has more to do with

the successes of the early twentieth century acting as a filter

between us and today's political world than with serious reflection

on what we need. There is nothing more misleading than old successes.

From

the late 19th century until around 1968, the world of popular

movements was dominated by broad mass movements with a broadly

overarching goal. In the developed countries of the North, the

labour movement was hegemonic; in the developing countries of

the South, the national liberation movements were. With their

alignment with state power and the world market, and the rebellion

against this by large parts of their base, they have lost their

hegemonic position and life has become more ”normal” – many

movements with sometimes diametrically opposed goals emerge without

anyone being able to gain the upper hand. As a result, they can

easily be played off against each other and the supremacy can

remain unchallenged.

Much ideologising has taken place around

this phenomenon. Supporters of the status quo have of course

applauded it and declared it

inevitable. But representatives of many popular movements have

also understandably defended the narrow interests of their movement

and asserted the supremacy of their ”identity”, thereby

implying the purity and incompatibility of all ”identities”.

This

is particularly true of the North Atlantic countries, where the

situation has so far not been entirely desperate, and where

movements have tended to be represented by ideologues. In the

South, where practical considerations and interests have dominated

and movements have been represented more by mass organisers,

it has often been easier to reconcile these interests, and there

has been less focus on ”identities”. For example,

at the Cúpula dos povos in Rio de Janeiro in June 2012,

it was not difficult to come up with reasonable joint action

programmes.

Focusing on interests and not on identities would

also help here in Sweden. Interests can be formulated to benefit

many, even

a large majority; identities must of necessity separate into

ever smaller coteries. We cannot do anything about what we are,

and it is therefore pointless to argue about. What we do, on

the other hand, can be influenced and made into policy. And as

an

unprivileged underclass, there is only

quantity to put behind the words. Anything less than a majority – and

a fairly large majority at that – is insufficient.

Building

majorities is therefore the only way to satisfy who you are.

***

The

popular mobilisations that led to previous Kondratiev cycles,

or ”good times”, hardly had these in mind when they

mobilised. They were fighting for justice and bread. The Kondratiev

cycles were an outcome, one that depended on the response of

elites to these mobilisations, and aimed to entice the more established

members of the movement to defect, or were at best compromises.

That

is how it will be now too.

There are endless injustices to mobilise

against, endless deprivations. From stingy pay deals contrasted

with what the bosses grant themselves,

to sell-offs of council housing and ore deposits to so-called

venture capitalists, to institutionalised humiliation when looking

for work or falling ill. The mobilisations will be about such

things. Around this, semi-permanent organisations will be formed,

large and small, which together will contribute to a popular

movement culture that creates a hegemony, which forces the authorities

to negotiate.

Negotiate on the issues at stake in the mobilisations,

but also on the long-term direction of society.

In general, it

can be said that the ability of the lower classes to extract

something from these negotiations has grown over time.

The first cycle, around 1800, based on canals and textile machinery,

gave citizenship to the middle classes but very little to ordinary

people. It was only the next one, around 1850, that began to

allow even skilled labourers into the fold. And only the one

around 1900 that recognised the citizenship of all (Europeans).

The

latest cycle, the one that took place after 1950, yielded the

most of all so far – citizenship for everyone worldwide,

at least in theory, and social rights both in the old industrialised

countries and new industrialising countries. But unlike in the

past, the results do not seem to have been lasting. I have argued

above that this was because the compromise was, if not overreaching,

at least on the wrong issues. That the compromise meant demobilisation,

and that the leaders of the popular movements set themselves

the task of ensuring that this demobilisation took place. Which

in itself meant that they had already acquired such a position

within the movement that this was possible.

A future compromise

must not be so short-sighted.

A future compromise must fulfil

the boundary conditions of the popular majority. And these boundary

conditions include the ability

to protect the gains made.

But also to maintain the ability to

move forward when necessary. For no Kondratiev cycle lasts forever,

and we were ill-prepared

for the end of the last one. Partly because the people’s

movement’s need for self-renewal was hampered by concern

for the smooth administration of the system.

Such care can usefully

be left to minions. The rest of us will have to move on. Left

to its own devices, a new Keynesian-inspired

investment policy will run amok and/or end in a new wave of

speculation worse than the last. It happened last time, it will

surely happen

again. Therefore, popular movements need to lead the development,

not become nice helpers as they were then.