|

Peoples' movements and protests |

|

|

DocumentMartin Luther King's letter from the Birmingham prisonMobilizationsWomen’s movementsFrench Revolution19th century republican movementThe black movement in the United StatesThe black movement in South AfricaNative American movementsBack to Civil rights movementsBack to main page

|

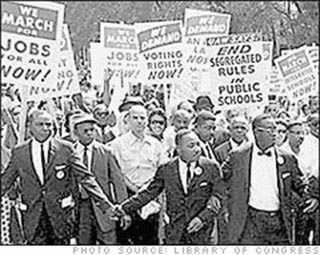

Black civil rights movement in the USA

The fact that people of African descent are pariahs in the United States is, of course, due to the fact that their ancestors were plantation slaves. When slavery was abolished during the Civil War of 1861-65 (a result of the slaves’ energetic contribution to the North Side armies), it did not mean that they became full citizens. They continued to be referred to the worst jobs, a system that in the poor southern states was guaranteed by repressive laws and official violence while in the northern states it was only strengthened by the whites’ contempt for the former the slaves. The first organization among the blacks was the churches. For a long time they were not a bit militant, but they would be in connection with the civil rights movement of the 50s and 60s. Political mass organization began in the 1920s, partly as a kind of consciousness movement run for a few years by the Jamaican Marcus Garvey, partly in the form of self-defense against white lynch gangs organized by the otherwise strictly lobby-oriented NAACP. In the 1930s, the black conveyor belt workers in the north organized in the unions. So did the all-black sleeper car service on the railroads, whose union became a leading mobilizer for Black equality. It succeeded to achieve that segregation was banned from enterprises that sold to the state. During the war, students in the Chicago CORE, Congress for Racial Equality, also engaged in sit-ins on segregated business in the North. But it was not until the blacks organized in the south that there was a mass movement. Here it was the churches that stood at the forefront, gathered in SCLC, Southern Christian Leadership Conference. They organized the successful boycott of buses in Montgomery in 1955 when the black movement first became front-page material, see picture above. This was not least because the movement insisted that the action was not just for the sake of the blacks but for the whole society. A little later, students and high school students (later organized in the SNCC, Student’s Non-violent Coordinating Committee) began to organize sit-ins in the southern states. They had great success locally, especially in the slightly more economically successful southeastern states, and the movement spread everywhere. Shortly afterwards, CORE began testing whether the law banning segregation on the intergovernmental bus network was actually complied with. But The Freedom Riders who did this were beaten and murdered – probably in large part because they came from outside. At the request of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the CORE and SNCC then switched to registering black voters in the poorest state of Mississippi, which provoked a formal reign of terror there from those in power. The government didn’t take any responsibility for law enforcement – except when it sometimes degenerated into pure riots, and the successes of this movement was slight. SCLC then chose another tactic: to provoke the racists to overreact and cause massive disorder. This was tried twice with brilliant success. In Birmingham in 1962, to protest against continued segregation, which the government legislated on after the police abused children in front of the TV cameras, and in Selma in 1965, to demand the right to vote for blacks, with the same result – see picture below. SCLC played skillfully on Kennedy’s and Johnson’s fear of chaos and of gaining a bad reputation in the new states of Africa.

From this time the movement began to disintegrate. The black middle class who acted via SCLC was pleased that the legal obstacles disappeared. The activists in Mississippi, who risked their lives to organize poor farmers, also demanded a higher standard of living, as did the slum dwellers of the big cities, which required more than changes in the law. To them, the American dream (which, for example, King appealed to) began to look more and more like a nightmare of everyday racism and ugliness. They started talking about black power. After the slum dwellers revolted in 1966-67 and the Vietnam War began to channel away welfare money into the army, the movement cracked along class lines, and the movement’s alliance with the unions broke. In addition, a super-militant black minority began to advocate offensive violence (vigilantly guarded by the media), which threw the white lower middle class into the arms of Nixon. A generation later, the black majority does not live much better than in the 50’s. Reading

|