|

Peoples' movements and protests |

|

|

MobilizationsThe peace of God and the municipalityFarmers against landownersCraftsmen and the revolutionary 1380sValdenses, Hussites and the struggle about the churchBack to Medieval movementsBack to Old movementsBack to main page

|

Valdenses, Hussites and the struggle for the church

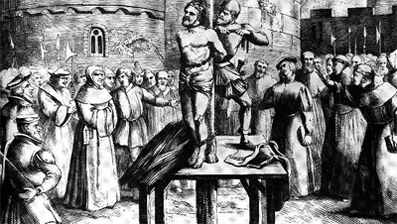

The Church was the only apparatus of power that extended throughout medieval Europe. Movements directed at its hierarchies and authorities were therefore the only form of popular movement that could become supra-regional. The ecclesiastical apparatus was long dominated by local potentates, much like those who ruled districts and cities. But at the end of the ninth century, a revolt against them was formed, by monks in alliance with poor city dwellers who wanted to make the church popular instead of upper-class friendly. This was assumed, just as the Communists a thousand years later, could best happen if the hierarchy and the obedience within the organization were strict and superior levels had power over subordinates. Within a few generations, this had led to corruption and to the higher clergy mostly craving for wealth and a comfortable life. Opposition movements were formed against this. As a rule, these arose among subordinate church dignitaries opposed the authorities and referred to Jesus’ example and the Bible. Dissatisfied craftsmen and peasants then joined, after which the authorities branded the congregation heretical – not because of what they said, but because they did not obey the authorities. Above is a picture of what that meant. Several such waves of opposition shook the church until the world market system made the conflict obsolete. The first was the Valdenses. They had been formed as strictly church-going laymen who wanted the pope’s permission to missionize against the non-Christian Cathars in the 12th century. But instead, they were scolded for being poor people who would aspire to the right to speak and persecuted because they missioned anyway. Gradually, they organized themselves into their own free church, which was strong in northern Italy and southern Germany. The next attempt was the Franciscans in the 13th century. To avoid heretical strife, Francis submitted to the pope in everything, but his followers were more radical and managed for about a hundred years to run a lay movement that was held together by its opposition to wealth. However, independence was broken in a series of heresy trials in the early 14th century. At the same time, the great feminist movement of the Middle Ages began to emerge, especially along the Rhine. They, the Beguines, did not make much of a fuss, but organized themselves into collectives that took care of themselves and kept at arm’s length distance from the hierarchy. They were also persecuted with heretical torches, but because they kept a lower profile, the persecutions were also more half-hearted and the movement lasted for a few hundred years. The most dangerous movement for the established rulers was the Hussites in the 15th century. They were a mixture of Czech nationalism and lay resistance to the luxury life of the ecclesiastical dignitaries. They were so strong in what is now the Czech Republic that they beat army after army that was sent there to defeat them; the founded cities, they revolutionized martial arts and the mobilized peasants and artisans to political power. Below is a picture of their dreaded tanks. They could never be completely overthrown, even if a more compromising wing prevailed due to the constant state of war, and compromised away the underclass aims in the movement. During the revolutionary time when the world market system broke through, around 1500, this form of opposition politics had become routine. Unfortunately, they then became increasingly irrelevant – the strong movements of Protestants and Calvinists who sometimes ruled all of Europe north of the Alps were all in one way or another co-opted by states on the periphery of the system and used to strengthen state power over the people. A bit like the communist movements used in the 20th century. However, they took an active part in breaking the royal dictatorships in two places and thus in the long run throughout Europe – in Holland and in England.

Reading

Publicerad av Folkrörelsestudiegruppen: info@folkrorelser.org

|