|

Peoples' movements and protests |

|

|

Mobilizations16-17 century piracyThe slave uprising in HaitiThe Chartists1848The First internationalThe Social Democratic PartyThe Revolutions 1917-19General strike in Hong Kong 1925-26The occupation of FlintThe welfare statePeronismThe boom of the 60s-70s in EuropeSolidarnoscThe metal strike in São PauloThe Hyundai strikeBack to Labour MovementsBack to main page |

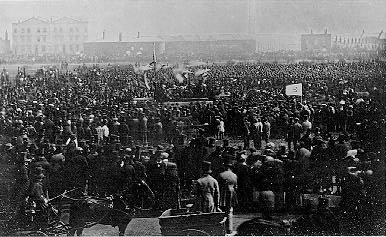

The Chartists

The English suffrage reform in 1832 was driven by the mobilization of workers in the 10s and 20s. But only the middle class got the right to vote. For the workers, the change of regime resulted in stricter police surveillance, abolished social insurance and forced labour. The Chartist movement began as a mobilization against the workhouses, a kind of prison where the unemployed were imprisoned. Many of these were stormed and demolished. But the workers also felt that they needed some unification. When the London Working Men’s Association proposed a call (or Charter) for universal suffrage in 1838, it was adopted as a program by local workers’ organizations throughout the UK. Despite an overarching programs, chartism remained entrenched in local culture. At the center of the movement, the industrial area between Birmingham and Manchester, the whole community was chartist. There were chartist pubs, chartist churches, the women organized chartist parties, the local politicians were chartists, and in 1844 chartists organized the first consumer shops in Rochdale. The unifying activities were the collection of names for the Charter, speaker tours where popular speakers performed, and the Chartist magazine Northern Star. Attempts were also made to organize people’s parliament days, but since it was expensive to participate in them, they mainly engaged the intellectual middle class who could not lead the movement locally, which is why they did not lead to anything. In July 1842, local chartists organized a general strike in northern and central England. The strike spread through demonstrations from city to city. This was the peak that the movement would never exceed. The petition was handed over to an uninterested parliament the same year and no new initiatives were ever taken. During the boom after 1848, the business community also began to buy out the more well-educated workers with higher wages, which is why the movement broke down. Chartism

developed the four-legged tactics that would dominate labor movements

until the First World War: Reading

|