|

Peoples' movements and protests |

|

|

Mobilizations16-17 century piracyThe slave uprising in HaitiThe Chartists1848The First internationalThe Social Democratic PartyThe Revolutions 1917-19General strike in Hong Kong 1925-26The occupation of FlintThe welfare statePeronismThe boom of the 60s-70s in EuropeSolidarnoscThe metal strike in São PauloThe Hyundai strikeBack to Labour MovementsBack to main page |

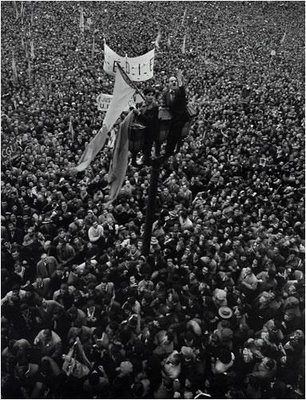

Peronism

An anarchist labor movement quickly sprang up among Buenos Aires immigrant artisans. But it was difficult to gain influence, because it consisted of immigrants that the Argentines considered foreign. Argentina’s key industry, the slaughterhouses, on the other hand, was organized late. Due to the large immigration, it was easy to fire union organizers and recruit new labor directly from the quay. But in the 1930s, slaughterhouses were bought by US capital and equipped with modern conveyor belt technology. And during the war, immigration ended. This reversed the trend. Because with a conveyor belt, a strike is easy. In principle, it’s just to turn off the power - yes, it’s enough for the power station to strike. And when the immigration had stopped, it was not as easy to dismiss the crew. At the same time, a regime came to power that was interested in national development, unlike the traditional Latin American free market regimes. Its Minister of Labor, Juan Perón, considered it good if the workers received higher wages because then more of the money would stay in the country. Throughout the war, a militant trade union movement at the slaughterhouses succeeded in improving working conditions with the help of selective point strikes and benevolent neutrality on the part of the state. Their success also spilled over to other workers who could follow suit. This divided the government, which feared the trade union mobilizations, and Perón was dismissed in 1944. The workers who saw their ”representation” in the government threatened went on strike and mass demonstrated in the streets, and in the presidential election they voted for Perón. Subsequently, the exchange became leaner. The real labor movement leadership was sucked into government posts or silenced in some other way. The strike leader and organizer of the 1944 protests, Cipriano Reyes, first became a senator and was later chased into exile for fabricated crimes. The workers became accustomed to trusting benevolent authorities, which became less and less benevolent over time. Only after the national development policy had burst in the mid-70s due to rising debts did they become militants again, so militant that military dictatorship and mass murder were required to crack them. Reading

|