|

Peoples' movements and protests |

|

|

MobilizationsThe peace of God and the communeThe war resistance around 1900The Algeria movement in France50-60s nuclear resistanceVietnam War Resistance in the United States80s nuclear resistanceMobilizations against African civil wars

Back to Peace movementsBack to main page |

50-60s nuclear resistance

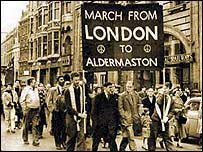

The popular movement that succeeded in breaking the total dominance of the US and Soviet governments over the public debate in the central countries was the movement against nuclear weapons between 1957 and 1962. It had roots in two traditions, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. One was the British Labor Party periphery of women’s movement, cooperatives and idealistically colored churches. It was the cooperative women’s guild in the London suburb of Golders Green that first started the discussion about whether it was reasonable to deal with a weapon that spread highly toxic emissions even in peacetime. It was within this tradition that the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was formed in 1958 – it was a fairly elitist committee of self-appointed and self-renewing celebrities that presupposed the formation of independent but subordinate committees locally. The CND saw it as aiming to hold talks with the Labor Party to get this to abolish the British nuclear weapons. A similar environment

in the United States later formed the National Committee for a Sane

Nuclear Policy with the more ”moderate” requirement

to stop the bomb tests. The demonstrations quickly became spectacular successes with tens of thousands in Trafalgar Square and with spillover effects in many countries in Europe (including Sweden, where a CND-like mobilization – the Action Group against the Swedish atomic bomb – actually stopped an ongoing nuclear weapons program). An activist culture spread throughout the industrialized world, whose advantages and disadvantages we still see today. And, again, the Cold War ideology fell into disrepute, much thanks to nuclear resistance. Yet the movement was not very successful in its own terms: once the United States and the Soviet Union had agreed to end nuclear tests in the atmosphere and started a tradition of discussing armaments before deciding on them, people became accustomed to nuclear weapons and the movement fell asleep in mid-sixties. Richard Taylor has captured the weakness of the movement in the concept of ”middle-class radicalism” by which he means focus on individual morality, insensitivity to economic realities and not least the inability to connect to already existing oppositional underclass subcultures. It is a legacy we still carry with us. Reading

|