|

Peoples' movements and protests |

|

|

MobilizationsThe peace of God and the communeThe war resistance around 1900The Algeria movement in France50-60s nuclear resistanceVietnam War Resistance in the United States80s nuclear resistanceMobilizations against African civil wars

Back to Peace movementsBack to main page |

Vietnam War resistance in the United States

Because the US government’s military support

for the military junta in South Vietnam started so stealthily from

1962 onwards, it took several years before a resistance was aroused.

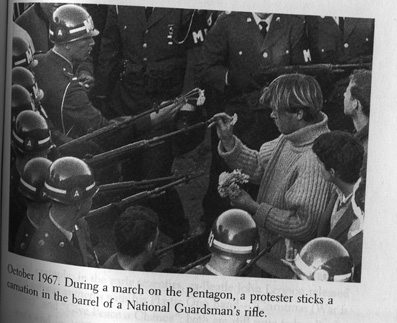

In the beginning, it was mainly established politicians who questioned

the wisdom of investing so much money. The first popular protests

started in 1965 when some convicts burned their summonses and went

into exile. First, the traditional peace movement, both fold opponents of nuclear weapons and the environment of Gandhians who had begun experimenting with non-violent actions during World War II and had great significance for the black civil rights movement. It was this movement that came up with the most practical proposals for action, and it was also the one that tried, in vain, to keep the sprawling movement together. Secondly, the liberal reformists in the left wing of the Democratic Party. At first, they acted mainly through mainstream political channels, but gradually become increasingly impatient. Thirdly, the now severely fragmented black civil rights movement. Both the traditional and the new black power fly believed that the war took resources from the civil rights struggle at home, and gradually also that it was unreasonable that so many blacks were killed in the war. Fourthly, the radical youth movement that has emerged in the middle class and that reacted, often violently and scandalously, to the culture of consumption and work and preferably expressed itself in cultural terms, the ”counterculture”. There was a strong mistrust between the counterculture and the liberal reformists. The movement culminated in 1967 with three initiatives. First, a mobilization for a giant demonstration in Washington, ”the Mobe”. It would be much smaller than what the organizers intended, only about 50,000 participants, perhaps mainly because it was eventually be completely dominated by one of the participant groups, namely the counterculture. Second, the initiative to launch a peace candidate for the 1968 presidential election. It was slow at first, but after the successful Vietnamese New Year’s offensive, everyone realized that the government had lied and McCarthy’s campaign was running like a top. Which lead to all candidates talking about imminent peace and that Nixon after his victory begans peace talks, if only for the sake of appearance. Thirdly, a decentralized but widespread and well-organized military refusal that was gradually spreading among the troops in Vietnam. Conscripts fled, deserted, refused to fight, shot their officers and took part in demonstrations so that the army into the 70s was totally incapable of fighting and was taken home. Instead, the bombing war was escalated. After 1968, the resistance to war was demobilized, despite the fact that more and more people were distancing themselves from the war. This was assumed to be mainly due to the fact that organized resistance to war had been limited to the middle class, talked about individual morality and good conscience and not about how much war costs the majority. But eventually the liberal inter-parliamentary campaign took its toll – a majority of congressmen eventually realized that the war was too expensive and stopped allocating tax money, after which it ebbed out in 1975.

Reading

|