|

Peoples' movements and protests |

|

|

MobilizationsJesus and solidarity in everyday lifeMuhammad and the revolutionary communityZhu Yuangzhang and the Secret SocietyIndia: anti-bureaucracy stolen by the intellectualsBack to Movemens against empiresBack to Old movementsBack to main page |

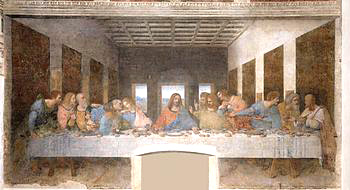

Jesus and solidarity in everyday life

The tradition of resistance in the western Mediterranean had a long history. The Jews as a group seem to have been a peripheral population that only became known when it defended itself against Egypt. When world trade established trading cities there, they defended themselves against them as well. The focus of the conflict was usually the indebtedness to various financial institutions that was caused by the harsh taxation. The goal was a nation-state welfare policy, in the pursuit of justice and equal rights for all. But in a world increasingly dominated by military empires, over time that policy seemed impossible. The one who then came up with something radically new was a carpenter, Jesus. He emphasized that the solution to people’s problems was not state policy but popular solidarity in everyday life. In addition, he stated that this did not only apply to his own national group but to all people. Around this program, local communities, congregations emerged, which, among other things, functioned as non-profit insurance funds. The communities were united by an increasing public that subsequently encompassed the entire Roman Empire and far into the neighboring empire of Persia. Not least successful was the Christian principle of caring for one another. During the two great plague epidemics that raged 165-180 and 251-270, the Christians did this, and survived, while the Gentiles looked after themselves and died. Christianity suddenly appeared enormously attractive. After a few hundred years, this public is estimated to have covered about 15 percent of the empire's inhabitants, increased to perhaps 25 after the epidemics. Among them were poor city dwellers who were most interested in maintaining human equality, security and justice, but also the empire’s foremost intellectuals whose main interest was to build intricate ideologies that legitimized the whole thing in the currently common language. The Christian community was sometimes regarded by the state as a dangerous apparatus of power that was persecuted, but sometimes it was tolerated if it reported what it was doing. Similarly, the Christian community’s attitude toward the state varied — some Christians supported it, others resisted more or less on the grounds of human equality and justice. At the same time, the empire encountered increasing economic problems and difficulties in financing an overburdened state apparatus. One of the power contenders, who appeared around the year 300, Flavius Constantinus, concluded that it was a real-politically smart move to ally with the Christian community. It also turned out to be so and it gave Constantinus victory in the power struggle. Unlike other communities in the empire, it was universal, did not identify with any specific group or nationality, and therefore provided broad support. Constantine was, of course, most interested in cooperating with the pro-state phalanx of Christians, who benefited in every way – including tax exemption and governmental positions – while the state-criticals were persecuted. This gave rise to violent fighting within the Christian movement. In particular, those critical of the regime were concentrated on the outer edges of the empire, e.g. Egypt and Syria, which in time would contribute to the success of the Muslims. A

more peaceful way of showing resistance to the state’s

ever stronger control over the movement was to form alternative

societies

where the early Christian spirit would be revived. The first

monastery was formed just a few years after Constantine’s

takeover. These monasteries gradually became very rich and

powerful, thanks to their

cohesion and work discipline. Of course, this led to new

conflicts, new alternative societies (with roughly the same

effect) but also to

the Christian movement strengthening its grip on society

by becoming strong in production as well. Reading

|